How we achieve equal access to pharmaceutical treatment

We’ve written recently about the prevalence of overprescribing, and how people of color are at higher risk for certain types of overuse, such as antipsychotics for dementia in nursing homes. But people of color also experience underuse of high-quality medications to treat chronic conditions.

For example, Black individuals with atrial fibrillation are significantly less likely to receive direct-acting blood thinners (the safest, most effective type of blood thinner) than white patients. People of color are also less likely to receive buprenorphine for opioid addiction and more likely to report underuse of diabetes medications because of cost. And during Covid-19, Black and Hispanic/Latinx individuals were less likely to have access to antibody therapy or other novel treatments.

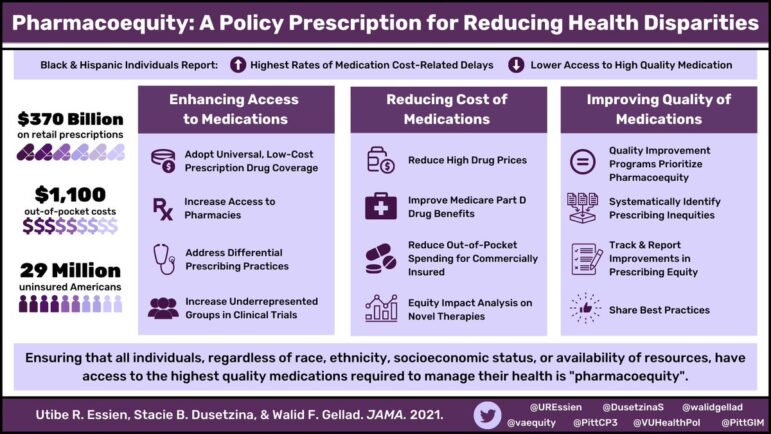

In a recent viewpoint in JAMA, Dr. Utibe R. Essien and Dr. Walid F. Gellad at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Dr. Stacie B. Dusetzina at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine coin the term pharmacoequity, which means “ensuring that all individuals, regardless of race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or availability of resources, have access to the highest-quality medications required to manage their health needs.”

Achieving equal access to affordable, high-quality medications is essential for reducing health disparities in the US. Essien et al offer policy solutions to address all three of these factors: access, cost, and quality of care.

First, we need universal coverage of prescription drugs. Millions of Americans are uninsured or have insurance that doesn’t cover all of their drug costs. Among Americans with Medicaid, 10% say they do not take their medications as prescribed because of the high cost. For uninsured Americans, it’s 14%. To achieve pharmacoequity, we need to insure everyone and fill the gaps left by insurance.

While there have been many proposed solutions to lowering drug costs, there has been little analysis of how these policies would impact disparities in drug access. Conducting equity analyses of these policies should be part of the process, to ensure that they don’t further widen racial disparities.

Even with universal drug coverage, pharmacy deserts create inequities in access. Essien et al write, “Decades of racial segregation through redlining, neighborhood disinvestment, and exclusionary zoning laws have left many individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups residing in communities with limited access to pharmacies.” The pharmacies that do exist in formerly redlined communities also tend to be independent pharmacies, which generally charge higher prices. Investing in pharmacies in underserved communities is essential for expanding access.

Of course, people can’t access prescription medications that they aren’t prescribed. Prescriber bias, even unconscious bias, can lead to disparities in access to medication. For example, Black patients with severe chronic pain are less likely to be given medication than white patients. Bias baked into medical algorithms can also result in less care being given to people of color for the same conditions.

Addressing differences in prescribing practices will require better transparency and accountability; tracking racial disparities in prescribing for health systems and making pharmacoequity a quality metric would help. Essien and colleagues also recommend improving access to medical specialists in underserved communities and using electronic medical record alerts to promote evidence-based prescribing for all patients.

“Underuse and overuse can affect the same country, the same health organization, the same hospital, and even the same patient.”

Vikas Saini et al, The Lancet Right Care Series, 2017

It seems counterintuitive that underuse and overuse could exist within the same population, but unfortunately this is very common. Structural racism creates and maintains the conditions that impede access to many affordable and high-quality medications for people of color; but at the same time these conditions put people of color at risk of overuse of medications like antipsychotics for dementia.

Essien et al assert that pharmacoequity is just one step toward health equity. “While pharmacoequity is necessary, it is not sufficient alone to achieve health equity without addressing the structures and policies that have left marginalized populations without sufficient resources to lead healthy lives.”