Uncovering health disparities by race, ethnicity, and education

Measuring and tracking health outcomes is essential for identifying gaps in care and improving health. But overall measures of outcomes can often hide large health disparities by race, ethnicity, and education. By disaggregating these data, we can start building a roadmap to better health for all.

Racial disparities by state

The Commonwealth Fund recently updated their “Scorecard on State Health System Performance” with metrics for health outcomes, health care quality, access to care for five racial/ethic groups: Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI); American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN); Black; Latinx; and white.

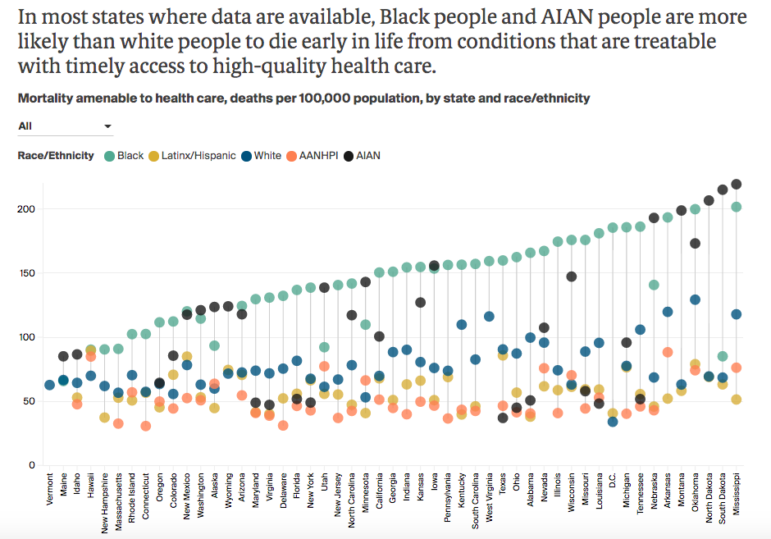

The new metrics show wide variation in health outcomes and access by ethnic group across states. For example, in some Southern states, the rate of death from conditions that are treatable with access to timely care was about 0.2% for Black individuals. Comparatively, in New England states, 0.09-0.1% of Black people died from conditions amenable to care. However, there are significant disparities within states, even those that do well overall. For example, in Connecticut and Massachusetts, Black individuals are nearly twice as likely to die from preventable conditions compared to white people, and three times as likely compared to AANHPI individuals.

The racial/ethnic breakdown by state shows some clear patterns. In every state, either Black or AIAN racial groups had the highest rates of mortality amendable to care. In almost every state, AANHPI or Latinx racial groups had the lowest rates of mortality amenable to care.

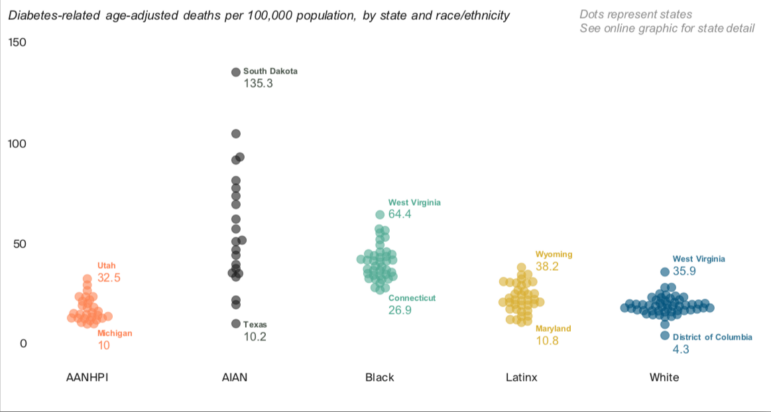

Looking at other preventable health conditions shows that we have a long way to go in reducing health disparities in every state. For example, the highest rate of deaths due to diabetes in white people in any state (0.036% in West Virginia) isn’t much higher than the lowest rate of deaths due to diabetes in black people in any state (0.027% in Connecticut). The greatest variation in deaths from diabetes is within the AIAN group, ranging from 0.01% in Texas to 0.135% in South Dakota.

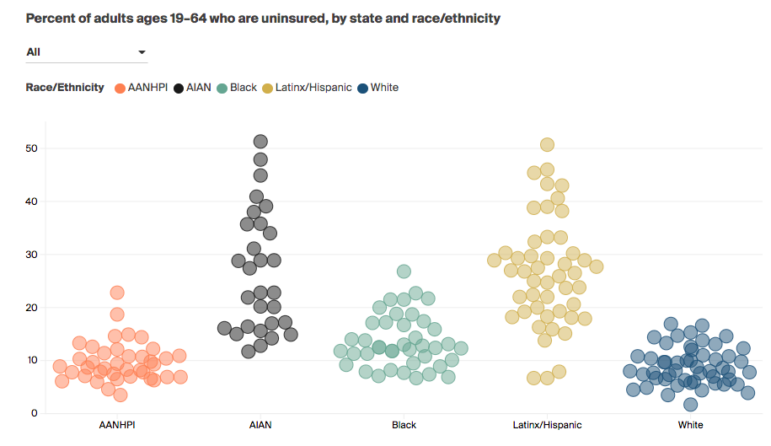

The Commonwealth Fund also found significant variation in access to health care, particularly among Latinx and AIAN individuals. Oklahoma has the highest rate of uninsurance for white adults under 65 (16.9%); in 44 other states, the rate of uninsurance for Latinx adults is greater than that. Even in Massachusetts, which mandates health insurance coverage, the uninsured rates for Black and Latinx adults under 65 (7.1% and 7.5%, respectively) are more than double the rates for AANHPI and white adults (3.5%).

Covid-19 disparities in race and education

Researchers have documented significant racial disparities in rates of Covid-19 infection and death, due to differences in neighborhood crowding, housing access, ability to physically distance, rates of chronic health conditions, and lack of access to health care, all of which have their roots in systemic racism.

However, it’s less well known how education levels, gender, and race intersect when it comes to vulnerability to Covid-19. In a recent study in JAMA Open, Justin Feldman and Mary Bassett at the FXB Center Health and Human Rights at Harvard University examined these issues.

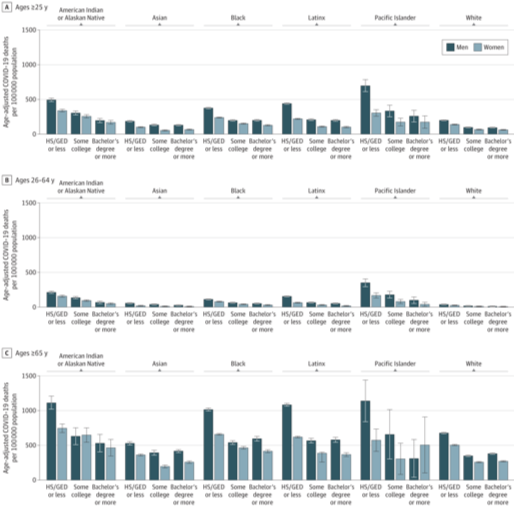

Feldman and Bassett used Covid-19 data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to look at rates of age-adjusted mortality from Covid-19 across subgroups of race, gender, and education in 2020. They found that across all racial groups and age groups, those with a high school education/ GED certificate or less had higher rates of Covid-19 mortality compared to those with more years of education.

However, even having high levels of education was not protective for most racial minority groups. College-educated Black, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Latino men died at about the rates of white men with just a high school education. And Covid-19 age-adjusted mortality rates for Black women exceeded those of white women at every education level; Black women with college degrees died at a rate 5.4 times higher than white women with college degrees. The authors calculate that if all racial and ethnic groups had the same Covid-19 mortality rates as college-educated white people, there would have been 71% fewer deaths among people of color.

This research shows that when it comes to Covid-19 risk, we have to consider numerous social determinants of health and how they intersect. While people of all races with lower levels of education are more likely to die of Covid-19, higher education doesn’t close racial health gaps. Eliminating these racial and class health disparities is essential to creating better health outcomes for all, during the pandemic and beyond.