HPV protection or cancer vaccine? Putting Gardasil in context

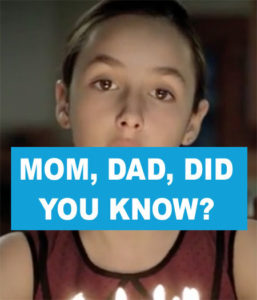

In the mid-2000s, Merck ran advertising campaigns for their Gardasil vaccine encouraging young women to protect themselves against cervical cancer, or admonishing parents for not vaccinating their children early enough. These ads tout the life-saving potential of Gardasil as “the only cervical cancer vaccine.”

But how did Gardasil become a cervical cancer vaccine when its primary utility is protecting against certain strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV)? We spoke with Dr. Samantha Gottlieb, whose upcoming book, Not Quite a Cancer Vaccine: Selling HPV and Cervical Cancer, explores the public health and cultural context in which this vaccine was marketed.*Since the original posting of this article, Merck has come out with a new Gardasil campaign that more accurately portrays the risk factors and consequences of HPV.

HPV or cancer vaccine?

Even before Gardasil was first approved, Merck was marketing it as a cervical cancer vaccine rather than a way to protect against HPV. Gottlieb attended a continuing education session for doctors who specialize in gynecological pathologies, funded by pharmaceutical companies including Merck. During the session, doctors were asked, “Wouldn’t it be great if there was a vaccine to prevent cervical cancer from HPV?”

After Gardasil’s approval, advertisements came out encouraging young women to get the vaccine to be “one less” victim of cervical cancer and telling parents to vaccinate their children. To fend off controversy, Merck “very deliberately avoided talking about sexuality,” says Gottlieb. Instead, they used the “cancer vaccine” angle to lobby state legislators to make it required in public schools.

However, this strategy backfired when parents and legislators caught wind of the lobbying, and Gardasil became caught up in the nationwide debate on vaccine safety. Ten years after Gardasil’s approval, only 50% of adolescent girls have received the vaccine, making it one of the most underutilized vaccines in the country.

Education or marketing?

When asked about lobbying legislators or their alarming ads, the makers of Gardasil maintain that they are raising awareness about HPV and educating the public. “When we talk about interacting with states at the government level, our actions have always focused on one thing: education. The message was, ‘Here’s what you should know about the virus,” said Beverly Lybrand, former Merck VP and manager of the HPV franchise, in a 2007 interview with AdWeek. Should drug companies be our main source of information on HPV?

Indeed, few people knew anything about HPV before Gardasil came out. However, Gottlieb questions whether drug companies should be the most prevalent source of information on medical conditions. Merck’s advertising campaign has essentially shaped what the public knows about HPV for the past ten years, which has led to some good and some not-so-good outcomes.

Raising awareness (and fear)

Before Gardasil, HPV was rarely discussed with patients, because it was extremely common, there wasn’t much patients could do about it, and most of the time it didn’t lead to cancer. Since Gardasil was approved, the vaccine has reduced the prevalence of HPV in young women, which is a great development. However, the incidence of cervical cancer and mortality from cervical cancer in the U.S. have remained almost exactly the same, at the low rate they’ve been since Pap smears have become more accessible and routine.

“These ads create anxiety and fear when nothing in existing gynecological practice has changed!”

Professor Samantha Gottlieb

However, that’s not what you would think by watching Gardasil commercials. Merck’s campaign makes cervical cancer seem impending, terrifying, and preventable only by the vaccine. The ads neglect to mention that Pap smears and the HPV test are the most effective ways to catch and prevent cervical cancer. “These ads create anxiety and fear when literally nothing in existing gynecological practice has changed!” says Gottlieb.

The early advertising campaign also left out other types of cancer caused by HPV that can affect men, because the vaccine was only approved for women at the time. This unnecessarily gendered HPV as a disease that just affects women, missing an opportunity to increase awareness of and reduce rates of HPV in men.

What should we be doing?

Gottlieb is decidedly not against the HPV vaccine, but she thinks there is much more we could be doing to reduce the incidence of cancer caused by HPV – for example, increasing access to regular Pap smears and advocating for a male HPV test, as there is none currently recommended for men.

In the absence of honest discussions on difficult topics, drug companies fill the void of information. “The marketing around Gardasil tried to oversimplify very complex discussions about vaccines, sexuality, and cancer prevention,” says Gottlieb. These are discussions we need to be able to have with our children and our doctors, to prevent more HPV and cancer.

Despite Merck’s insistence that scary ads are educational, there’s no need to stigmatize HPV or make people afraid. “We should be telling people, you will likely get HPV and will probably be okay,” says Gottlieb.