Incidence vs mortality: Which cancers are we overdiagnosing?

Over the past several decades, the medical community has made many positive advances in cancer prevention and treatment, leading to reduced deaths from cancer. However, for some types of cancer, we have not improved mortality rates despite pouring billions of dollars into early detection efforts.

Which types of cancers are we preventing, which types are we treating better, and which types are we overdiagnosing? A new analysis in the New England Journal of Medicine helps provide an explanation. In this analysis, Dr. H. Gilbert Welch, senior researcher in the Center for Surgery and Public Health at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and colleagues looked at 40 years of data, from 1975-2015, to find patterns of incidence and mortality of various types of cancers.

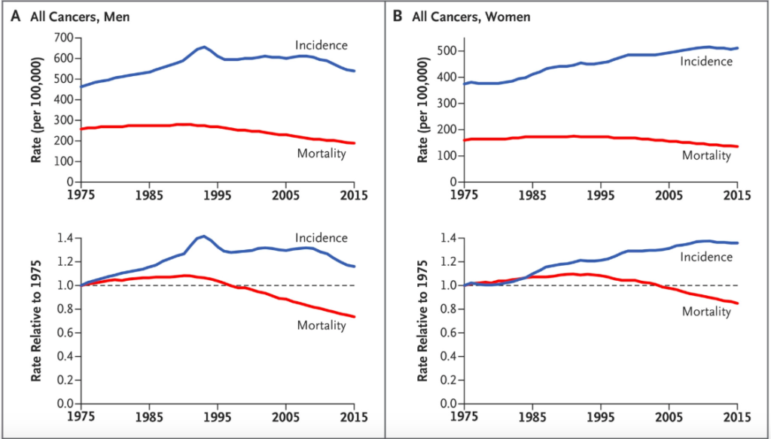

Comparing the incidence of cancer (the rate at which cancer is found in the population) and mortality from cancer (the rate at which people die of cancer) shows how well we are identifying and treating different types of cancer.

For example, if the incidence and mortality both decline, it means we are finding cancer in fewer people and fewer people are dying from it. If incidence is stable and mortality declines, it means that the rate at which people get cancer is unchanged, but we are better at treating it. However, if mortality remains stable while incidence goes up, it means that we are likely overdiagnosing this type of cancer. In these cases, we are finding more cancers that never would have killed people, exposing patients to unnecessary tests, surgeries, cost, and stress.

The good news is that overall cancer mortality has declined since 1975 (by about 30% for men and 20% for women). Much of this has to do with efforts to reduce smoking in the U.S., which decreased both the incidence and mortality rates from lung cancer. We are also doing much better at treating Hodgkins Lymphoma and Chronic Myeloid Leukemia, as mortality rates have declined while incidence remains stable.

Welch’s analysis also shows good news regarding stomach, colorectal, and cervical cancers, for which both incidence and mortality have declined since 1975. For cervical cancer, declining mortality can be explained by effective screening and treatment of precancerous legions. Colorectal cancer incidence and mortality both were in decline before screening started and both measures continued to decline over the next decade, indicating that this type of cancer is not being systematically overdiagnosed.

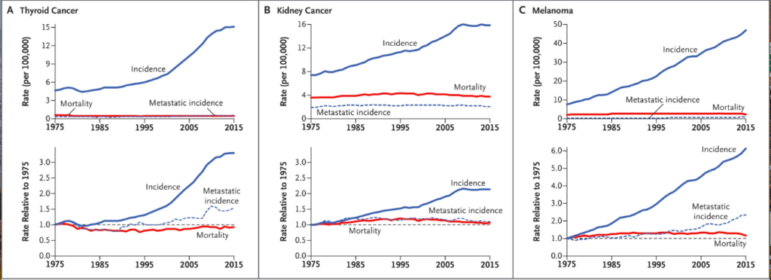

However, for thyroid and kidney cancer and melanoma, the data show signs of overdiagnosis. While the rates of metastatic cancer incidence and mortality have remained stable since 1975, we are finding many more of these cancers now than in previous decades. New scanning technology has increased the rate of incidental findings of small harmless thyroid tumors, leading to more “findings” of thyroid cancer. Similarly, increased melanoma screening and new dermatology tools have increased overdiagnosis of melanoma.

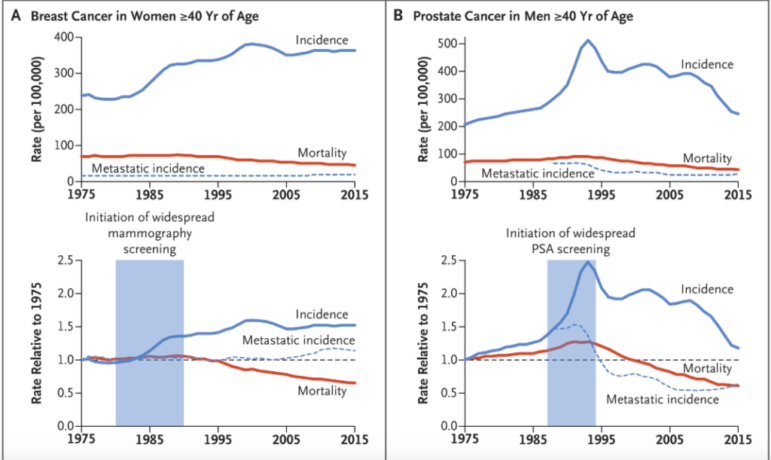

When it comes to breast cancer and prostate cancer, analyzing the results of the data gets tricky. Unlike other cancers, the incidence of breast cancer and prostate cancer increased after screening was implemented, and mortality from these cancers decreased. On first look, this could indicate that screening is helping, by finding cancers and treating them before they harm patients. However, this could also point to overdiagnosis, in which harmless cancers are found and treated, while better treatments for these cancers are increasing survival.

For breast cancer, the incidence of metastatic cancer (cancer that has spread to other parts of the body) was relatively stable since 1975, which indicates that overdiagnosis of harmless breast cancers is likely. For prostate cancer, the volatile incidence rates point to the effects of changes in screening practices over the years, not true cancer rates. In both of these cases, the more we screen for cancer the more we find, making it look like more people have cancer when in reality we are just searching harder. Despite the assertions that breast and prostate cancer screenings “save lives,” Welch et al. find that declines in mortality are more likely due to improvements in cancer treatments rather than early detection efforts.

Welch and colleagues emphasize the importance of looking not only at incidence rates (how much cancer we find) but also at metastatic incidence and mortality to get a clearer picture of how well we are doing at preventing and treating cancer, and to know which cancers we are overdiagnosing. They also call for more detailed data on cancer findings to include how the cancer was found. Cancers found through patient symptoms and signs are more likely to be true cancer than cancers found by chance on an unrelated scan or through systematic screening. Knowing the way in which we are finding cancers can help us better understand which cancers are being overdiagnosed.

However, knowledge is only the first step to preventing overdiagnosis, and alone it is likely not enough. In an op-ed in STAT, Welch acknowledges that “the horse is out of the barn when it comes to overscreening.” Convincing health care institutions and companies to stop screening for certain cancers will be difficult, considering that increased medical testing and procedures makes them more money. It will also be difficult to disabuse the notion that “cancer screening saves lives,” even though this is only true for some types of cancer.

The way forward to better survival from cancer is through reducing rates of smoking and other cancer risk factors and investing in research toward treatments that improve cancer survival (not just surrogate endpoints). “If society tries to procure improved population health from the medical-industrial complex, we won’t buy more health, but simply more testing,” Welch says.